ABM Archive Website

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS ARCHIVE MATERIALS FOR HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

For up-to-date information, including our latest appeals, news, and resources, please visit our current website.

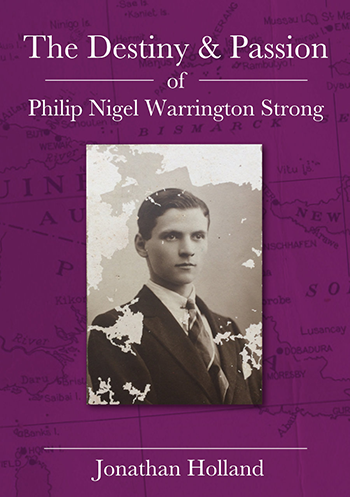

Book Review: The Destiny & Passion of Philip Nigel Warrington Strong

Ivan Head’s recommendation: Buy and read this book.

|

December 2019

This large, superb book thoroughly, compassionately and critically explores the life of this major religious figure in twentieth century Papua New Guinean, Australian and British life. The book is of sufficient excellence to be of interest and stimulation in more than one field: biography, spirituality, history, history of mission and in Hugh Mackay-like studies in the demographics of change and continuity in Australian life.

The book divides into three parts, each well researched with informative and interesting footnotes. Part One (1899-1936) covers Strong’s life in England from birth to consecration as Bishop for British New Guinea, as it was then named. Strong was ordained a Priest in 1923 after war service in France. He was an authentic Anglo Catholic. He was consecrated Bishop in 1936 for British New Guinea; the region more correctly known by its Australian (since 1905) administrative term The Territory of Papua. Holland gives an informed and interesting account of the history of Western dominion across the island and islands (p. 131) and Australians generally and our elected leaders would do well to be more familiar with this. Reaching forward to 1962 for a moment, Bishop Strong would comment vigorously by radio broadcast within Australia about the newly independent Indonesia (1949) now led by Sukarno, and the claim for sovereignty over the former Dutch New Guinea or West Papua. Strong’s criticisms may be as pertinent today and were clearly prescient and well-founded (p. 351). He made SMH headlines with them, earning a rebuke and apology from the yet to be knighted PM, Robert Menzies.

Part Two covers his twenty-six years as a missionary Bishop in Papua and includes the traumas of WWII and the Japanese conflict, and also of the catastrophic eruption of Mt Lamington in 1951, in its own way as disastrous and costly as the War: as impactful on the cause if his church. I note here four lines from New Guinea, by James McAuley (foundation Quadrant editor), from his poem New Guinea, derived from time in New Guinea (1944-1960) that overlaps with Strong’s.

Bird-shaped Island, with secretive bird-voices,/Land of apocalypse, where the earth dances,/ The mountains speak, the doors of the spirit open,/And men are shaken by obscure trances.

Part Three of the book covers Strong’s eight years as Archbishop of Brisbane, from which position age obligated him to retire in 1970 – given that an extension to his time in office was not granted. He was Primate of the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania from 1966, following Archbishop Gough’s (Sydney) unexpected resignation.

Holland describes a man who lived and breathed the Church and its faith to the exclusion of all other interests. He remained unmarried. Many unmarried; men and women served as a life work in the mission field of PNG. He lived and worked through a time when gender matters in ministry had a clear binary and binding resolution and where marriage for life or unmarried celibacy were the unquestionable options; and where the remarriage of divorced persons was not permitted in the Church of England.

Strong is shown in some ways to be an autocrat in the Anglo Catholic domain of the Church of England tradition and that may have meant something like the old mantra for Bishops: ‘being in Holy Orders means that I give the orders.’ The book is good enough to enable that tension between consultation and autocracy to be explored since it is a theme as old as St Benedict and his Rule, or St Philip Neri and his Oratory. A trajectory for thematic study lies across these three men. Holland handles this theme well across Strong’s life. His strong mindedness had given his own Bishop pause for thought in his English parishes.

Holland, a Bishop in the Diocese of Brisbane, fairly and justly outlines the issues that marked Strong’s seven years in Brisbane and as Primate of the Church of England in Australia, or the Anglican Church of Australia as it would become. It is clear, that without projecting anything, Holland has caught the sense of a national church that has always had major divisions and conflicts; from before Strong’s time until the present. He gives a clear sense of Strong as an older world traditionalist in the strong and fast flowing stream of a modernity that he was neither at home in nor comfortable with. His time in Brisbane marks great changes in the mores of Australian and global life. This is aptly illustrated in the passage (p. 407) where the new-fangled world of television means that The Forsyte Saga goes head-to-head with Sunday Evensong and rates more highly for too many. In the same years ‘Strong’s diaries . . . are potted with refusals to those seeking re-marriage.’ (p. 429)

In the domain of ‘what the Church believes and lives by’, Holland’s discussion of the impact of Bishop John Robinson’s Honest to God on Australian and global Christian life in the nineteen-sixties is helpful and worthy of study (pages 429 434). Strong’s response to it is in some way a litmus test of the times. It may no longer be presumed to be adequate for a Bishop to have a faith that is ‘unquestioning and simple’ (p. 434), or indeed authoritarian in any sense. To be authoritative demands more. Perhaps the nineteen-fifties were the last simplicities of Australian life. Sixty years later it is a very different human world.

Thus, this book could form major set-reading for graduate entry Theological students and as advised in-service training for priests. Theological Colleges are properly interested in learning from Australia’s recent past and particularly with reference to our nearest neighbour to the north. But the book also tells Australians about themselves and about the changes (not all for discernible good) that have marked our past century. The Destiny and Passion could be paired for instance with The New Guinea diaries of Philip Strong, 1936-1945, edited by David Wetherell and James McAuley’s writings on New Guinea. Holland on Brisbane in the nineteen sixties is fascinating.

Holland’s book spans the now little-remembered time when Papua and the Mandated Territories (under German control until the close of WWI) were effectively part of Australia and part of the British Empire. It reaches forward through the WWII years and the long decades before the Whitlam Government and the transfer of powers to an independent PNG in 1975. It covers the journey that in part led to that point, and the increasing role of the Commonwealth of Australia in PNG following that War and its brutal locoi across the islands.

The following themes (at least, and indeed in addition to the primary biographical one) can be explored with deep interest through the book: themes that align and overlap chronologically with the long history of the Australian and then Anglican Board of Mission and its work in PNG.

- The Church of England as the then dominant social form of Australian life (form in the sense of formal element, as used by the Hungarian-Australian philosopher Julius Kovesi). Religion was not so much a private matter but part of the civil, and civic matrix of a domain that participated in Empire until well after WWII. In some ways, perhaps the Church of England was like ‘standing for the Royal Anthem in the cinemas’, something which this reviewer remembers from those days.

- The death of Anglican missionaries in PNG at the hands of the Japanese in WWII, their reception as Martyrs, and the very serious, personal and damaging conflict over whether Strong had erred in permitting or encouraging the missionaries to stay at their posts in the conflict zone is worth more study.

- The deadly eruption of Mt Lamington and its advent remains as an issue for Theodicy and mission. Its ‘paired document’ would be Pope John Paul II’s Encyclical on suffering Salvifici Doloris.

- Strong’s prescient decision to make George Ambo a Bishop and the momentum towards a nascent, fully independent PNG Church. This ordination seems to have challenged long-held boundaries and markers of difference between missionary and those receiving the mission, and changed the basic symbolisation expressed in the matter of ‘who ate with whom, and who drank tea with whom’: an issue as old as the Letter to the Galatians in New testament times. Holland is illuminating on this matter. The Wikipedia entry on George Ambo (Sir George Ambo KBE 1922-2008) notes that he was ‘born among the Somboba people, one of seven children (with five sisters and a brother), the son of the clan’s specially trained and initiated master of traditional dances. He learnt to dance in turn, and had become a leader of the dance before he started school, which he did in 1934, at an Anglican mission school.’ I note McAuley’s reference to the earth that dances.

- The Australian Board of Missions (Anglican Board of Mission since 1995) is seen to have a key role in Strong’s mission and to be a major financial supporter. Holland covers this dimension, and its tension between ‘control and episcopal independence’ very well. There is a wider story to be told about the ABM’s role in PNG from beginnings in1885 through to its current, effective role today in partnership with the Anglican Church of PNG. Holland’s book shows very clearly that Philip Strong’s energetic and faithful trajectory was a key part of that long, fruitful story.

- The book also in its own way raises the question of the form of Christianity within the matrix of the then dominant British Empire, and broader imperial modes of thinking and behaviours. Immense changes to these pre-conditions run from 1885 through WWI, WWII and into the present. This has major implications for the Church of England and her global ‘expressions’ or embodiments in independent ecclesial units of Christianity across much of the globe. In that sense, the move towards autonomies in the PNG church can be seen as part of a larger movement towards autonomies, and within Australia itself. Within Australia, The Church of England in Australia and Tasmania changed its name to The Anglican Church of Australia (1981), having adopted a new national constitution in 1961-1962; at the time of Strong’s appointment to Brisbane.

For all that, this Anglican Church today seems more fragmented and parlous than the Church of England and the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania that Strong knew and gave himself to without reservation. This is clearly seen in Holland’s succinct account of the origins of the Anglican mission in PNG in the ABM’s sponsored mission of Albert McLaren and Copland King (1891, Dogura).

What he says is timely one hundred and thirty years later. He notes that these two men, one Anglo Catholic and one a convinced Evangelical ‘Theologically . . . could not have been more dissimilar’ but each was ready to work with the other. Holland notes ‘They had met by accident in a railway carriage in rural NSW and conversed over some hours as the train rattled along.’ (p. 136)

Holland’s book will become the major resource for any study of Strong’s life and his ministries. It has an important place in the wider study of mission in New Guinea from 1891 to the present. Much work remains to be done to understand better the realities of the encounter between the British and Australian carriers of the Gospel, and the peoples then immersed in the primeval domains of a land with its own gods, spirits, demons and powers – and of new ways of engaging in the mission that is Christ’s before it is ours.

Finally I must add that in the background of Strong’s extraordinary service in PNG lies the indefatigable work of the ABM or Anglican Board of Mission, without which core support, even the Bishop’s charism to lead and inspire and envision would have foundered.

Holland makes clear throughout the book that it is the ABM in the background that is working collegially and in the common yoke of Christ to make the Diocese and the Mission work. That holistic and demanding support continues in new ways to this day.

Jonathan Holland, 2019. The Destiny & Passion of Philip Nigel Warrington Strong. Lakeside Publishing.

< Back