ABM Archive Website

THIS WEBSITE CONTAINS ARCHIVE MATERIALS FOR HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

For up-to-date information, including our latest appeals, news, and resources, please visit our current website.

What should the National Anglican Church’s reconciliation priorities be?

|

ABM’s Reconciliation Coordinator Mal MacCallum reflects on his program and would like to hear from interested parties about how ABM and the National Church can respond to and act for Reconciliation.

1. Providing opportunity for parishes and dioceses to look at their own local histories to uncover the stories of the church interactions with the local First Peoples and work toward reconciliation at their community level.

2. Being a National voice for ways to address the extremes* of the demise of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultures. (* youth incarceration, self-harm and suicide rates being totally out of proportion with the non-indigenous population clearly indicating a major crisis in these communities nationwide)

During the last two months I have had opportunity to travel to three different far flung locations nationally to meet with people involved in ministries with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ATSIP).

- Perth to meet with some Nyoongar people,

- Yamba to take part in the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Anglican Council (NATSIAC) and

- the Northern Territory to be part of the Bishop’s Award Program in Katherine where people in ministry from all parts of the Territory are brought together for Christian leadership training.

As I reflect upon these experiences and the now 18 months I have been in this role, I can see more clearly priorities that ABM, as a National Church organisation, must highlight and strive toward supporting more strategically.

There is clearly ATSIP dispossession, less than humanitarian care, and in extreme cases, blood on the ground from Anglican Church interaction with the First Peoples throughout much of the history of the last 230 plus years in Australia. The Anglican Church is not alone as an institution in these horrible Australian realities, but given its foundation of love, forgiveness and ultimate reconciliation, it must progressively lead more in the national turning of the tide toward genuine reconciliation of the First People and those who came here subsequently.

Yagan and the Nyoongar people

A story from the Nyoongar people in Western Australia illustrates some of this revelation. Yagan, a proud young Aboriginal man of the Nyoongar Nation in what is now known as the Swan Valley, paid for his cultural pride with his head (literally) for standing up against the invasion and invaders.

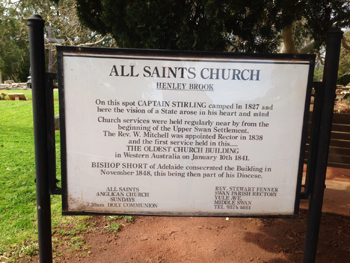

All Saints Henley Brook in the Parish of Swan is the nearest Anglican Church to this sad and revealing story of our history. The church is within 5 km of the Yagan Memorial, a moving tribute to the complex but clear example of dispossession by our forebears irrespective of the needs and “title” of the obviously present original inhabitants. The church, the oldest in WA, is on the site where Captain James Stirling ran out of navigable water as he initially explored the possibilities of a colony.

The sign pictured below tells the story of the colonial mindset toward subsequent dispossession and ultimately Yagan’s atrocious murder.

|

My recent journey to WA gave me insight to this story at a local level, but also helped me reflect on our national story. So as the mood for reconciliation apparently gains momentum, this local parish wants to set about a time of healing and community building toward a better future. This reconciliation is for the Nyoongar people living locally, those scattered afar and the “new settlers”, the non-Indigenous people connected to this parish.

I met with parish priest Stuart Fenner and three parishioners. I mostly listened as they related what they knew and felt were important issues to consider in the collision of the two cultures.

Complexities abounded but mostly what emerged was a lack of communication and understanding of the original local people by the church and community historically, and a recent desire to address that lack. There was a poignant moment when one of the group revealed that she (a regular parishioner) had only recently begun to discover her own Nyoongar heritage, and so the story had become so much more real, personal and fundamental to her existence.

After quite a time of their discussions I felt things were drawing to a close so I asked if I could make some observations. They agreed and so I put three questions on the table for their community to consider:

- What would have been said in the church the Sunday after Yagan’s beheading?

- What would be said in the church if that happened locally today?

- Had the parish considered consulting the local Nyoongar people to have a formal connection between the church and the Yagan Memorial? (The site of the church represents the beginning of the invasion into that part of Nyoongar country and so a connection there is an appropriate public statement of recognition, apology and healing toward reconciliation.)

The first priority that ABM, as a National Church organisation, must highlight and strive toward supporting more strategically is to provide opportunity for parishes and dioceses to look at their own local histories to uncover the stories of the church interactions with the local First Peoples and work toward reconciliation at their community level.

If you have read this far thanks! Could you please let me know what you think of this priority? If you would like me to come and explore it locally with your parish, diocese or community, contact me at reconciliation@abm.asn.au

The second most obvious priority is to do with the future.

A very sobering report was put together over a period between 2012 and 2013 about the huge increase over the last twenty years in the rates of suicide and self-harm amongst First Peoples youth. That report ‘The Elders Report into Preventing Indigenous Self Harm and Suicide’* is distinctive given that it has only First Peoples input with no bureaucratic modifying or dilution. Fundamentally, it calls for resources for the reinstatement of elders taking young Indigenous people onto country for cultural education as part of any school system they are part of.

A recent experience in a town with a large Aboriginal population, followed by a bush experience, brought some of the concerns of this report home to me. It doesn’t really matter which town or bush setting it was that I visited. The observation of lots of Aboriginal people idle around the streets, apparently waiting for something, does not appear to be a good environment for young people to be forced into. Prior to non-Indigenous people arriving here, this phenomenon would not have existed as it does now and if it had in any form culturally, it would have been far more beneficial then what occurs today.

It is a fact that there is a large younger population growing up in ATSIP communities and a decreasing level of elder style leadership at the same time. This unbalance is having negative educational and capacity of leadership effects. The worst case scenarios are the self-harm and suicide statistics we are becoming increasingly aware of and alarmed about. Good things like health, education and employment are continuing to sustain a huge gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. At the same time incarceration rates, self-harm and suicide rates are climbing steadily, alarmingly and are totally out of proportion with comparable population numbers amongst the non-Indigenous communities.

Going Bush

|

| Kewelyi kids |

The second half of this experience was going into the bush to a small dry (no alcohol) community to catch up with a friend and his family. Being totally unprepared for what I would find upon arrival, I happily bought a little food to take with us thinking I was being generous to my humble friend who opted not to tell me that much more was needed.

We arrived late at night to a small camp which consisted of a two room shack and a smaller one room shack. Ten children aged between 6 and 13 years streamed out of the bigger space and devoured all of the food we had and still went to bed hungry I am sure. The problem was the family had chosen to live 45 km out of the influence of a non-dry bigger community. No one in my friend’s absence (three days) could drive and so food had run out. The ten children were not all my friends’ children but they had “adopted” 9 of them from family adults who were in town or elsewhere in dysfunctional states.

We woke early the next morning and some of the boys and we men went off to fish and shoot (legally) breakfast. We came back with a goanna and a fish, a few mouthfuls for each child at least for that day.

At the same time, given the isolation, the water system the community relies on was not working for at least some of the days my friend was away. We went straight to the pump a few minutes into the bush and fortunately, I had a jerry can of diesel in my vehicle so the pump was restarted to replenish water tanks near the houses. The children and older lady were not able to manage these tasks.

These 10 kids living more traditionally are not experiencing firsthand the demise of their culture in town. They have a blended yet more traditional life out of town. I can’t honestly say at this point how effective the education of these kids for their futures is yet I can say they were delightful kids apparently not obviously affected by what was going on in town. Where will those kids be in ten years? What will have changed for them to be able to avoid the dangers of town so they can rise above these problems of the west’s worst features?

Can the Anglican Church nationally do something about this situation? Can we be a voice toward the Federal and State governments readdressing education systems for our First peoples, particularly those with clear access to more traditional opportunities to be developed toward adulthood?

I believe so, and from a couple of senior Bishops and Archbishops I believe the momentum and motivation is growing.

Being a National voice for ways to address the extremes* of the demise of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultures. (* youth incarceration, self-harm and suicide rates being totally out of proportion with the non-indigenous population clearly indicating a major crisis in these communities nationwide)

I would like to explore this further and so call upon any individuals and diocesan organisations who agree to contact me with interest to be involved please.

If you have read this far thanks! Could you please let me know what you think of this priority? If you would like me to come and explore it locally with your parish, diocese or community, contact me at reconciliation@abm.asn.au

Mal MacCallum

Reconciliation Coordinator

October 2014

*https://bepartofthehealing.org/EldersReport.pdf

< Back